My Father's Hand, My Mother's Pages

On letting my parents exist together peaceably inside my memories

Why am I writing about my father inside this space which is meant to accompany my writing about my mother?

Well, today is Dead Dad Day—the 32nd anniversary of my father’s death which is the central theme in my recently published essay collection, All Things Edible, Random and Odd: Essays on Grief, Love and Food.

And of course, my father was married to my mother. Together they had two daughters, me and my sister. I’ve written already about the difficulty of coming face-to-face with the ugliest facts of their long but largely unhappy marriage, and in that post, I say that this knowledge makes me

hate my father (who I loved and hated and still love and hate and this is the way it goes with some fathers, I guess) a little more.

In that post, my heart is angry and bruised on behalf of my mother, who did her own angry bruising of me and my sister, and if I’m being honest, our father, too.

Alcoholism leaves bodies and lives pummeled and bloody. My mother acknowledged and accepted this in the years after she embraced AA. She did her best to make amends to the people who remained in her life—me and my sister just for starters. But she didn’t get the chance to do that with our father.

He didn’t really get to do that with her either, though there was a Christmas—the year of their divorce, I think—when he wrote her an uncharacteristically heartfelt and honest card apologizing for his part in the demise of their marriage and asking her to give his love to her family—her mother, brothers and sisters. I wonder what that meant to her. I wonder if it diffused some of the resentment she felt toward him.

Something I don’t focus much on in my book is the fact that my father and I had been estranged from each other for most of the year before he died. I was more than mad at him for reasons that seemed proportional to my 20-year-old sense of injustice. We did reconcile—kind of—in the hallway of the ER before he was taken to the ICU. He couldn’t speak then—the virus we didn’t yet know he had was settling into parts of his brain that made communication difficult or just weird. He was mad at me—really mad, red-faced-screaming mad—because I had sent him a letter letting him know that I expected reciprocity and respect from him, and because I had used the word “fuck” like 17 times or something to get my point across. In the ER, he tried to convey all of this to me, and I swatted him away with a glib tone that belied my terror at his sudden illness, “We’ll talk about this later, Dad,” assuming, of course, that we would. We would not. He died 9 days later. But before he did, I at least got my own experience of his uncharacteristically heartfelt honesty when, as I was leaving his hospital room to go home one evening, he grabbed my hand and said, “I love you.” That was the last thing he ever said to me and I’m grateful for it.

On Dead Dad Day, I cook food I imagine I could have shared with my very cosmopolitan father. Some years it’s been a complicated recipe, others—particularly when I was in the throes of new motherhood—something much simpler. Green olives chopped into cream cheese and spread on stone wheat crackers. White Castle hamburgers. Decent New York pizza (when I could find it).

The book goes into depth on this in the essay “Dead Dad Day,” which chronicles my dynamic with him around food. Another, “American Home Cookbook,” does that same with the dynamic between him and my mother. The essay characterizes my father as lazy and selfish and demanding. It takes my mother’s side when he critiques food she cooks and serves him. “It’s all brown,” he says about one meal, prompting a dinner guest to angrily present him with a bottle of green food coloring, effectively shutting him up/down.

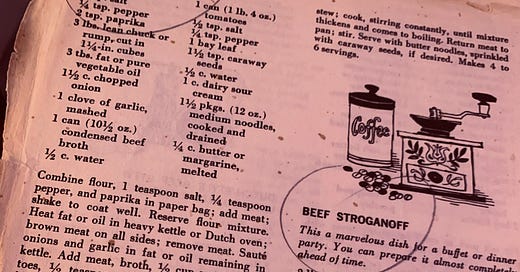

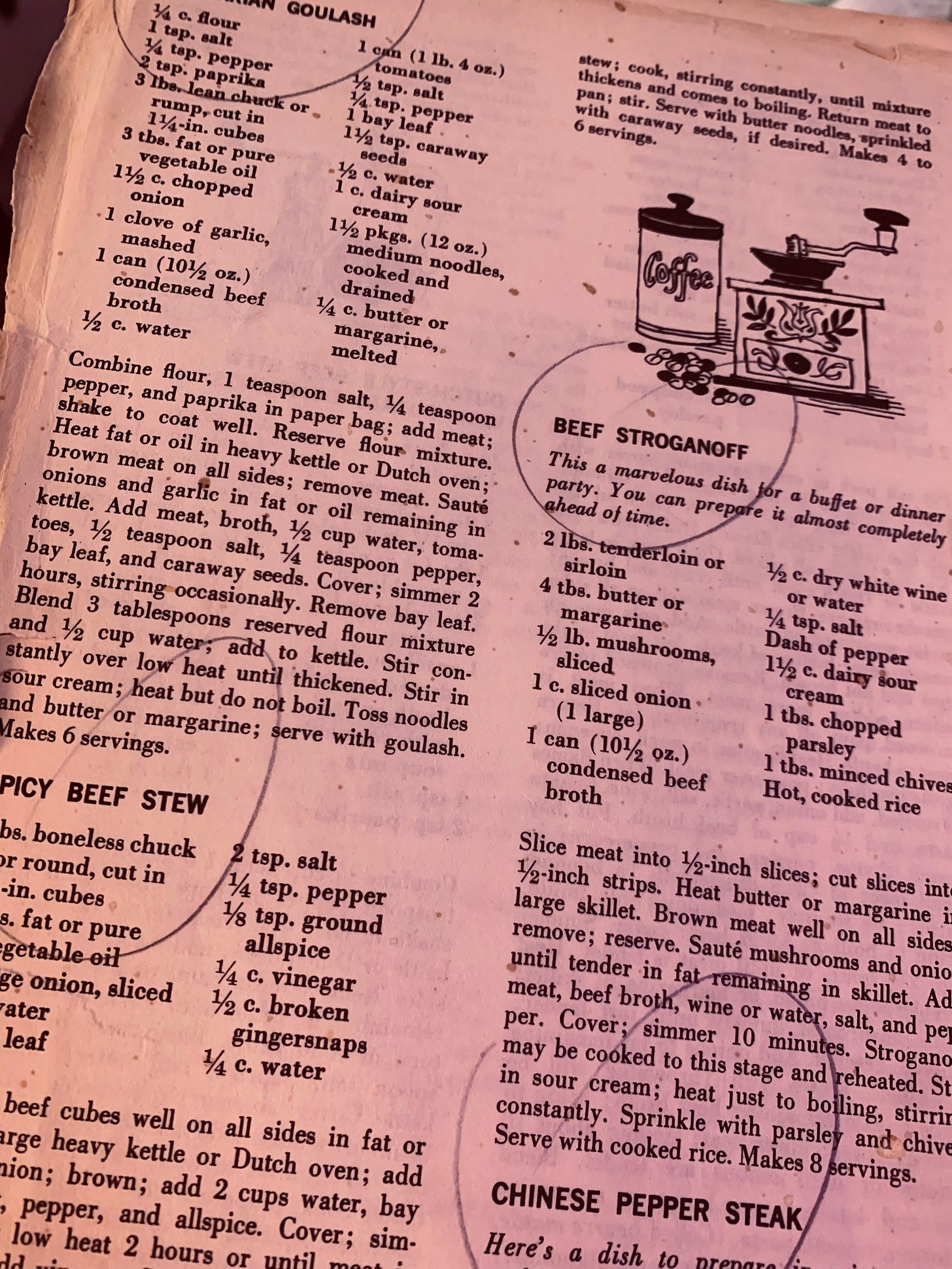

The American Home Cookbook of the title is a real cookbook, the one I learned to cook from. My mother’s copy of it is falling apart from years of constant use. It is filled with my father’s hand, circling recipes he wanted her to prepare for him. In the essay, I describe this as yet another act of domestic oppression he inflicted on my mother, who was no #tradwife at heart, though it sure looked like it for years.

Yesterday, my son reminded me, “Tomorrow’s Dead Dad Day. What are we cooking?” And I swallowed a silent groan because I am SO SICK OF MAKING FOOD DECISIONS FOR OTHER PEOPLE…just like I’m sure my mother was on the day of brown food and on lots of others. But then I remembered: I have her copy of the American Home Cookbook. Maybe I would find one of my father’s hoped-for dishes circled in there to make for dinner.

I did not. I mean, I could have, but who wants All-American Meatloaf or Boiled Beef with Horseradish on a 90-degree August day?

But here’s what I did find: a new way to think about those circles. What if, instead of seeing them as coercion, I call them collaboration? Surely there was a moment when she would have been delighted to cook something for the man she loved. I know well how satisfying that can be. Maybe the circles are all from an early time in their marriage (I am telling myself today and what’s the harm in it?) before the already ugly got even uglier. Maybe the circles are a metaphor for continuity or inclusion or safety.

Maybe.

In this version, my father sits on the couch on a Sunday afternoon. Cup of coffee next to him, cigarette burning in the ashtray as usual, with the cookbook open in his lap. He’s reading through it like a novel, pausing at the delicious places, allowing his vast culinary imagination to lead the way.

I have read cookbooks this way. It was for many years a favorite thing to do.

As the “Dinner Decider” in my family for the last twenty years, I am sometimes astonished by the trust it takes for one to hand over their meal choices to another person regularly. There’s a kind of intimacy to it. That’s the part I like.

But it’s exhausting, too, and so this year, instead of deciding on the Dead Dad Day meal on my own, we four went to the Asian market near our home with a budget of $25 each and the directive to pick out foods we think my father would have loved/we would love to try. I truly didn’t care if that meant we ate a meal of seaweed snacks, quail eggs, dried fish, and Pocky sticks.

But instead, we got all of this, plus a few other items not in the frame:

Dinner ended up being (and yes, I cooked it, happily):

a young coconut, opened with my biggest chef’s knife and my son’s brute strength

spiced watermelon seeds

a platter of oven-roasted taro root fries

pork and cabbage dumplings with rice and Sichuan chili oil

daikon salad

sauteed crown daisy greens

five-spice baked tofu

pork floss

It was an eclectic, delicious mess of a meal, and we still have a whole bunch of things in the fridge and freezer to make on a different night. (I’m looking at you, pork belly!)

It felt sweet to imagine making a meal my father’s hand selected out of my mother’s cookbook pages. And it feels better than it used to (it used to feel flat wrong), to imagine my parents in some kind of harmony with one another as a way of honoring my memories of them and understanding their places in my life.

My father’s birthday is at the end of October. Maybe I’ll make the Hungarian Goulash from page 160 with the Rice Pudding he circled on page 306. That sounds like a comforting fall meal.

At the end of tonight’s dinner, my son said, “I’m grateful for your father, with all of his flaws, because I wouldn’t be here without him.”

Yep. Me too.

I’m also grateful to the other man in my mother’s life, her husband, Gary, for giving me her copy of the American Home Cookbook after she died.

I absolutely treasure it.